My first introduction to Kent Russell was about two years ago, when I came across his essay “Island Man” in The New Republic.

In that piece, which is included in this immensely enjoyable debut book, Russell introduced the reader to Dave Glasheen, a man who spent much of his early life, and privilege, on building businesses and securing financial success – enjoying the spoils of capitalism and saying with some reflection that his family had never rented anything in their life; that is until he lost it all, about $10-million of net worth.

The society, which had allowed for Glasheen’s financial success deserted him as his fortunes sank, like rats fleeing to a passing barge. Until the point in 1993, when in a final attempt to connect to those white-collar dollars, he deserted himself on an island where he continued to live mostly alone into his old age.

“It was at least the first step, he figured. If a boat is foundering, you dry-dock it for repairs. Likewise, if you suspect your heart has a hole in it—take yourself out of the world.”

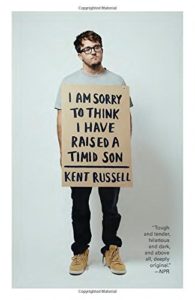

This sentiment of removing oneself is at the center of Russell’s new collection of essays, I Am Sorry to Think I Have Raised a Timid Son. Russell appears to have used this tactic to keep at arm’s length, trying to remain more objective than subjective, throughout stories that highlight the struggles of mostly white males feeling outcast from their otherwise privileged position and how that relates to his own struggles with his father, who clearly considers Russell that “timid son.”

In an opening essay about the war in Afghanistan, we see quite explicitly how it is that Russell removed himself from his family’s tradition of military service. Then, interspersed between journalistic pieces covering topics as far reaching as snake handling, professional hockey and The Gathering of the Juggalos, Russell investigates this familial myth of manly men who literally soldiered on in order to uphold a status quo stretching back to those same American revolutionary wars in which Daniel Boone was supposed to have said, “I am sorry to think I have raised a timid son.” The quote being about Boone’s own son, who hadn’t volunteered himself for the battle that claimed the son’s life.

The status quo Russell’s own father yearns for reaches back to the 1950s suburban American dream.

“You got a take on things. Like soccer, for instance,” Russell quotes his father. “You can see the future. I can only see the past. Still, I find it very hard to believe that Americans – American fathers – would give up head-busting for that pussy sport.”

Taking aim at the social expectations which might lead to the curious case of disenfranchising some white males – a sort of patriarchal out casting — Russell has embedded himself in a number of situations where men have made it their purpose to embrace, possibly even reclaim their more primal instincts, while also accepting they no longer occupy a place in mainstream society.

It isn’t really until mid-way through the collection, when Russell joins the Tom Savini Special Make-Up Effects Program, that he clearly outs himself for which camp he falls into.

“If forced to sketch a brief ethnographic portrait, I’d say this institution attracts mostly white males who dislike any reliance other than self-, who hate crowds, waiting, and the feeling of being a small piece of something greater, and who would refuse the steep and perpetuating cost of modern convenience if they could. Oh, and who still read print media. Simpatico, to say the least.”

To compare Russell in style to David Foster Wallace would not be inaccurate, although Russell is far less timid about self-reference than DFW ever allowed himself to be. Perhaps Chuck Klosterman would be a closer comparison.

In threading together several of his previously published journalistic pieces, Russell undertakes a keen examination of how his relationship with his own father ties the ends together, including father-son dialogue that is referential to both these essays in progress, as well as conversations deeply revealing about their relationship.

One thing Russell surely isn’t timid about is debasing himself or others; quoting his father he writes: “I know it’s your job to be a nibshit, but you have this habit of identifying me in stories and then misreporting the truth.”

The crux of Russell’s essays, of which some previously appeared in Harper’s, n+1, The Believer, The New Republic and Tin House; is that for all that remains to be written on the subject of subjugations and disenfranchisement (patriarchal or otherwise), no matter how disenfranchised he may see himself, he is still a white male with the advantage of being able to insert himself into other peoples lives without much reflection of how his presence changes the situation.

In the end, I’m left wishing Russell had shared some further insight into what it all means, but instead I felt like his father’s desire to defend the status quo wins out and that the only insight to hold onto was from Adam, an attendee of the Gathering of the Juggalos, who Russell quotes as saying: “You can write whatever you want about us, and everyone’s going to believe it. What difference does it make what I say? You’ve got the power. Plus, I give no shits.”

Maybe, Russell doesn’t feel a responsibility to take a stand in the face of his combative father, who eventually concedes to Russell, “I’m proud of you … And I guess I don’t have a history of telling you that,” and instead he just accepts that he is, in fact, OK with being that timid son.

Then again, maybe Russell accepts that he doesn’t have the power either, and thus just gives no shits.

The book is available on Amazon via this link: http://smile.amazon.com/dp/0804170444