THURSDAY, AUGUST 18th at 6:00PM

Book Launch Event: Poetry and Prose at Stauf’s Coffee Roasters – German Village

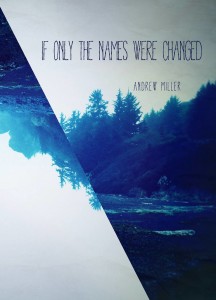

Join central Ohio author Andrew Miller for the official launch of his debut book, “If Only The Names Were Changed.” Miller turns his focus inward through poetic prose and dramatic digressions, dissecting his life using both surgical scalpel and sledgehammer, making deep cuts through layers of memories and misperceptions in search of some meaning behind a senseless loop of abuse and self-harm.

The event will be held at Stauf’s – German Village (627 S. Third St.) with several amazing (and funny) Columbus authors. Good words, books for sale, and some interesting conversation. Hope to see you there!

ANDREW MILLER is a freelance journalist and writer from Columbus, OH who has had work in Ohio Edit, Two Dollar Radio, The Seldom Review, Electric Literature, and Fruita Pulp. His first full-length book of essays, If Only the Names Were Changed, is now available through Civil Coping Mechanisms (2016). He has also published a chapbook, “You Must Know This” Digitalocracy Analogs (2016) and is in contract for a book documenting the struggles of veterans with Traumatic Brain Injury due out late 2016.”

The Storialist is HANNAH STEPHENSON, a poet, writer, editor, and instructor living in Columbus, Ohio She is the author of In the Kettle, the Shriek (Gold Wake Press), editor of The Ides of March: An Anthology of Ohio Poets (Columbus Creative Cooperative), and a poetry and arts blogger for The Huffington Post; her writing has appeared in publications that include The Atlantic, Hobart, 32 Poems, Sixth Finch, Poetry Daily, and The Nervous Breakdown. She is the founder of Paging Columbus!, a literary arts monthly event series.”

SOMMER MARIE STERUDis a writer, poet, instructor, and stand up comic living in Columbus, Ohio. She’s currently pursuing her Ph.D. from Kent University in Rhetoric and Composition while working as an associate professor at one of her alma maters, Capital University. Sommer spends her free time writing comedy with Johnny DiLoretto who she co-hosts a late night talk show with once a month at the Shadowbox Theater. She received her MFA in creative writing and poetry from OSU.

SCOTT NAVICKYis the author of Humboldt: Or, The Power of Positive Thinking (Chicago Center for Literature and Photography, 2014). His second novel is in contract and should be available December 2016. He attended Denison University and the University of Auckland, where he was awarded an Honors Master’s Degree in art history with a focus on photography theory. His work has appeared in Chicago Literati, HYPERtext Magazine, (614) Magazine, Fiction Writers Review, Necessary Fiction, ZO Magazine, Chaos + Words, and Loveliest Magazine. He currently lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Nancy Kangas lives in Columbus and is happy to field questions about the city. She writes and draws for Muse magazine, and often teaches poetry in residencies sponsored by the Ohio Arts Council. In addition to being a writer, she is also a flower grower, florist, and public librarian. She also has a background in Improv. For over a decade she edited Nancy’s Magazine, which tried to push the boundaries of what a variety magazine could and should do. She is a runner who prefers long distances because while running, she is able to figure out answers to creative, social and household problems.

For more information about events on offer from The Book Loft, check out http://bookloft.com/ or stop by their German Village location.